David Paulding reminds us of the growing risk of contact centre fraud, while providing his advice for how to stop it.

Fraud is a problem that costs the UK economy £193 billion a year, impacting every section of society and business from individuals running corner shops to multinational banks.

That calculates to £3,900 per adult and losses of £6,000 per second, and is an issue taken extremely seriously by business leaders as they strive to protect their customers and operations from criminals.

While technology has spurred the development of new methods of fraud, modern fraudsters are still using some of the oldest tricks in the book, including phone fraud.

Financial institutions and banks remain high risk as they provide a lucrative target for fraudsters.

Fraudulent calls made to contact centres are up 113% according to the latest figures from Pindrop, and banks and financial services organisations need to be braced for this trend to continue.

Companies are investing billions on bolstering their cyber defences, but the phone channel is often overlooked, making it the weakest link for hackers and fraudsters to exploit.

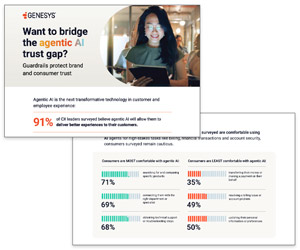

At a recent Business Reporter briefing sponsored by Genesys on preventing contact centre fraud in the banking sector, experts came together to brief leading CXOs from major banks on prevention and detection.

The expert view was that social engineering plays a huge role in fraudsters targeting call centre workers.

Bank contact centre employees have told that some attackers pretend to be forgetful or stressed to trick the call handler into helping them answer a security question.

Others take the opposite tact and are aggressive, intimidating contact centre staff and threatening to complain about the service they have received.

When the primary role of the contact centre agent is to deliver a good experience, it’s very hard to know when to treat someone behaving irregularly like a customer or a potential fraudster.

Fraudsters will try to exploit this, as they know that contact centre agents will go above and beyond to be polite and helpful.

Technology is helping. Simple tech like caller ID can tell the agent if a caller is not where they claim to be; and more sophisticated technology can alert an agent when a call comes from a suspect device.

But, pretty much every defensive method can be worked around or broken by a fraudster who is determined enough.

Fraudsters have become quite adept at gathering crucial information, including answers to common security questions such as mother’s maiden name, and from other sources.

For example, with social media it’s all too easy for people to find out details around birthdays, pet names, favourite places and things and even relatives’ names.

Furthermore, attendees noted that they were disappointed in how easy it was for fraudsters to acquire genuine forms of identification. Driving licenses, for example, are relatively easy to obtain for someone who is determined enough.

Asked whether loss prevention or brand protection was a bigger motivation to deal with fraud, most attendees at the event said that customer protection was actually the main driver, as fraud is one of the most frightening experiences a customer can encounter.

While attendees said that they were doing the best they can, all agreed that there were limits to what can be done.

The most organised fraudsters have entire call centres, filled with people paid to call banks and attempt to defraud them.

Increased layers of security checks were only a temporary solution, fraudsters can find a way round them all eventually, but that was what most banks are relying on for the moment.

However, customers don’t mind a bit of friction in the customer experience if it means that their bank is taking their security seriously.

One option that seems to appeal is a data privacy exemption exclusively for the prevention of fraud.

At the moment it’s very hard to thoroughly check a caller’s credentials because data protection laws strictly control where data can be stored and how it can be used.

With the introduction of GDPR (the General Data Protection Regulation) next year, those controls will become tighter still.

However, most attendees felt that real change could only be achieved with a new, stronger identification standard.

Some are arguing that the best option for this would be a government-mandated system, though most recognised that there has typically been reluctance in Britain to have a national identity card or something similar.

David Paulding

Nevertheless, one attendee pointed out that such a system is in place in the Nordic countries and they were among the world leaders in tackling fraud.

If governments are unwilling to step in, then perhaps banks should create their own ID system, it was suggested. Though, of course, obtaining one would require people to verify their identity, which might well mean them presenting other forms of ID that are not secure.

Author: Robyn Coppell

Published On: 15th Aug 2017 - Last modified: 16th Aug 2017

Read more about - Archived Content, Genesys